So Much to Say about Pres. Trump's Election EO, But Let's Start with Passport Possession

What the Survey of the Performance of American Elections says about passport possession

There is so much to say about President Trump’s executive order on election administration. Is it legal? Is it feasible? Is it good policy?

I have thoughts, but I also have data. Let me address one part of the feasibility question on the proof of citizenship, to the degree that passports would be allowable as proof.

I am currently writing a report on the 2024 Survey of the Performance of American Elections, a survey I have conducted every presidential election (and some midterm elections) since 2008. One battery of questions we have asked every presidential election except 2020 is about the possession of various forms of identification, including driver’s licenses, birth certificates, and passports. For this post, let me focus on the possession of passports.

Passport Possession

Among respondents to the 2024 SPAE—a representative sample of registered voters—56% reported possessing a passport, which is up from 44% when the question was last asked in 2016. Of those who reported having a passport in 2024, 13% stated that it was expired, and 2% indicated that it did not have their legal name. All told, 48% reported they had an unexpired passport with the holder’s legal name.

One important feature of the SPAE is that the sampling unit is the state, which means we can get a pretty good estimate not only of who passport holders are demographically, but also where they live.

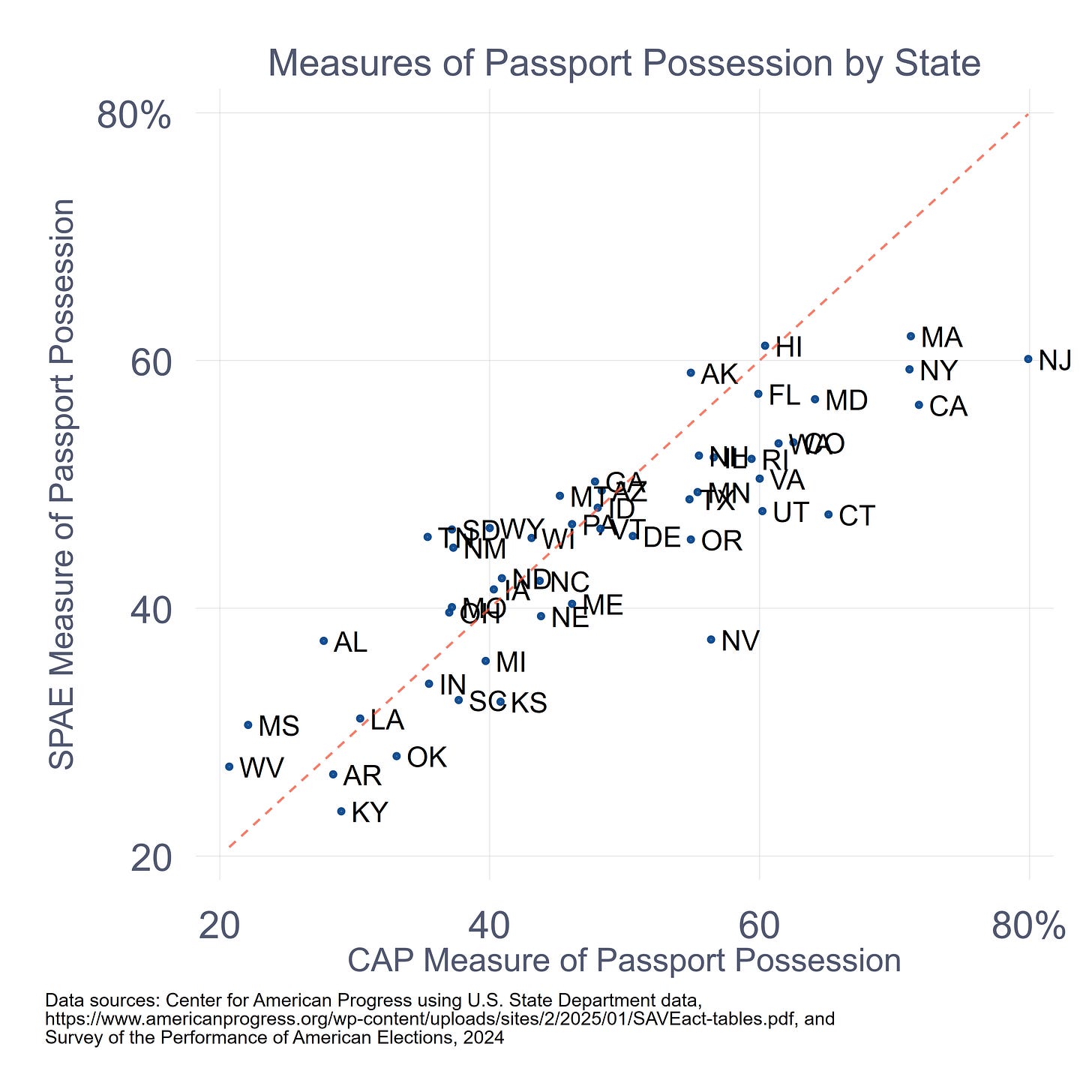

Below, I have plotted the percentage of respondents who reported having a non-expired passport in their own name in 2024 against the Center for American Progress’s estimate of the percentage of the whole population in a state that holds passports. Even though the CAP’s estimates are just that, estimates, and the SPAE’s estimates are based on self-reports, the two numbers line up pretty well, excepting that a few states at the high end of passport possession (Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, and California) show much lower rates using the SPAE measure than the CAP measure.1

It has been well established that passport possession is correlated with predictable demographic characteristics, particularly income and education. Those patterns are clear in the SPAE data. For instance,

56% of respondents with at least some college education reported having a passport compared to 30% of those with a high school diploma or less, and

68% of respondents with a household income greater than $70k reported having a passport compared to 31% of respondents with a household income less than $70k.

Nearly equal fractions of Whites (46.8%) and Blacks (47.2%) reported holding a passport. Hispanic (58.0%) and Asian (64.8%) respondents were more likely to report holding a passport than either Whites or Blacks.

I tend to focus on administrative issues when considering things like proof of citizenship, but we cannot ignore the political dimensions, especially since we have the data. Among Democratic respondents, 54% reported having a passport, compared to 44% of Republicans and 38% of independents and third-party respondents.

This partisan difference is not only because blue state residents are more likely to hold passports than their counterparts in red states. If we control for the “state effect” using a technique called fixed-effects regression, Democrats are still nine percentage points more likely to hold a passport than Republicans. This difference remains at five percentage points even after further controlling for education, income, age, and the respondent's race.

In other words, if passport possession were required to register to vote—and clearly, there would be other ways to establish citizenship—Democratic voters would be advantaged over Republicans.

What about Birth Certificates?

Another way to establish citizenship could be a birth certificate. This is a document many more people have than passports. The 2024 SPAE reports a much higher rate of birth certificate possession at 89%. Unfortunately, the SPAE did not ask respondents whether the name on their birth certificate was their current legal name. This is particularly important in light of recent news reports that have highlighted the difficulties married women, in particular, face when using their birth certificates to establish citizenship during registration. Additionally, a 2023 report by the Pew Research Center found that 79% of married women changed their names upon marriage, with an additional 5% hyphenating their names.

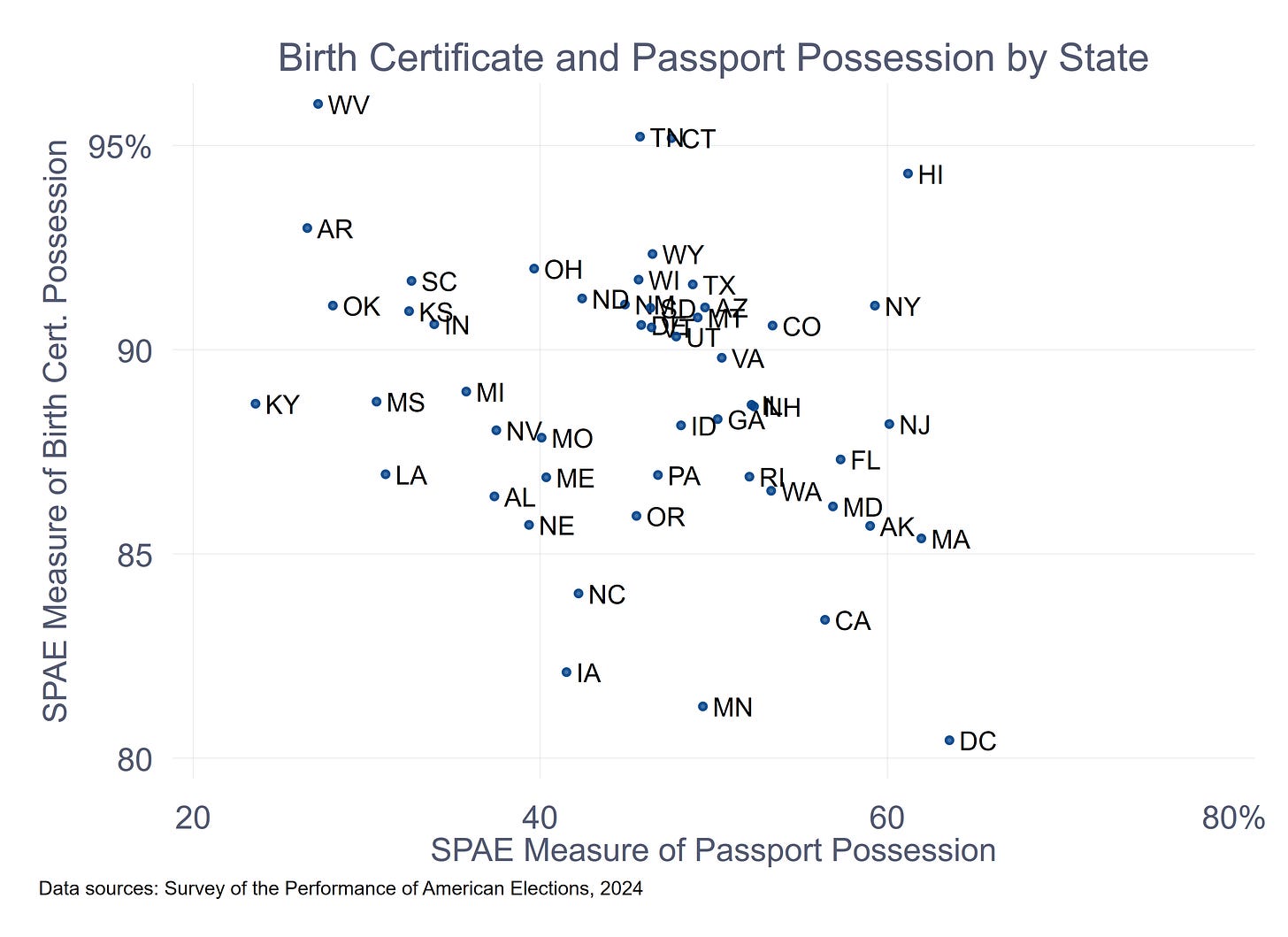

If there were not a huge disparity between men and women in whether the name on the birth certificate matched the legal name, the passport-possession disparity might not be so important. Leaving aside these important gender differences, state statistics on birth certificate possession are more equitable across states than those on passport possession, ranging from 80% in the District of Columbia to 96% in West Virginia. Of particular interest is the fact that states with higher birth certificate possession are generally those with lower passport possession, although this correlation is not especially strong (r = -.28) (See the figure below).

Additionally, possession of a birth certificate is not as demographically stratified as possession of a passport. For instance, 88% of respondents who did not attend college reported having a birth certificate, compared to 89% of college attendees. The same comparison holds for households with annual incomes below and above $70k. Birth certificate possession is nearly equal by race, with the notable exception of Asian Americans, 70% of whom report having a birth certificate compared to 89% of the remaining respondents.

Thus, if birth certificates could be counted on to have the correct name of all eligible voters, the problem of inequitable possession of passports might be solved, or at least close to being solved. Yet, that seems to be a big “if.”

How Hard Is Establishing Citizenship for Voting? Harder than You Think

There is much more to be said about President Trump’s executive order on voting. It focuses on a policy outcome that is universally accepted: only citizens should vote in federal elections, and only eligible voters should be registered.

There is no evidence that non-citizen voting, let alone registration, is widespread in America. Yet, many Americans are worried about the problem. We know from extensive research that Americans most concerned about this issue will not be convinced that the problem is minor by simply repeating statistics about how rare non-citizen voting is and why it would be perilous to non-citizens themselves.

American citizens are also not required to possess citizenship proof and to check in with authorities when they move. This is one area where Americans’ fierce civil libertarian streak, which is unique in the world, confronts the difficult problem of ensuring that not only are non-citizens kept off the voting rolls but also that all Americans can be assured of this fact.

Because of this, even if the executive order survives legal challenge, of which I have my doubts, we will have dealt with one problem by creating others. There has to be a better way—but that’s a topic for another day.

This difference may be because the CAP’s statistics are based on the U.S State Department’s statistics, which record where passports were issued, while the SPAE measures where passports are held. Note that the CAP does not report statistics for the District of Columbia, presumably because the issuance rate in D.C. is well above 100%.

US passport or non specific passport?